In 1972, William T. Creasman, MD, established the Division of Gynecologic Oncology in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology (OB-GYN) at Duke, becoming the division’s first chief. This coincided with Duke becoming an officially designated Comprehensive Cancer Center by the National Cancer Institute, then under the leadership of William Shingleton, MD (now deceased).

Four years before, Duke had already made its first big mark in the gynecologic oncology field.

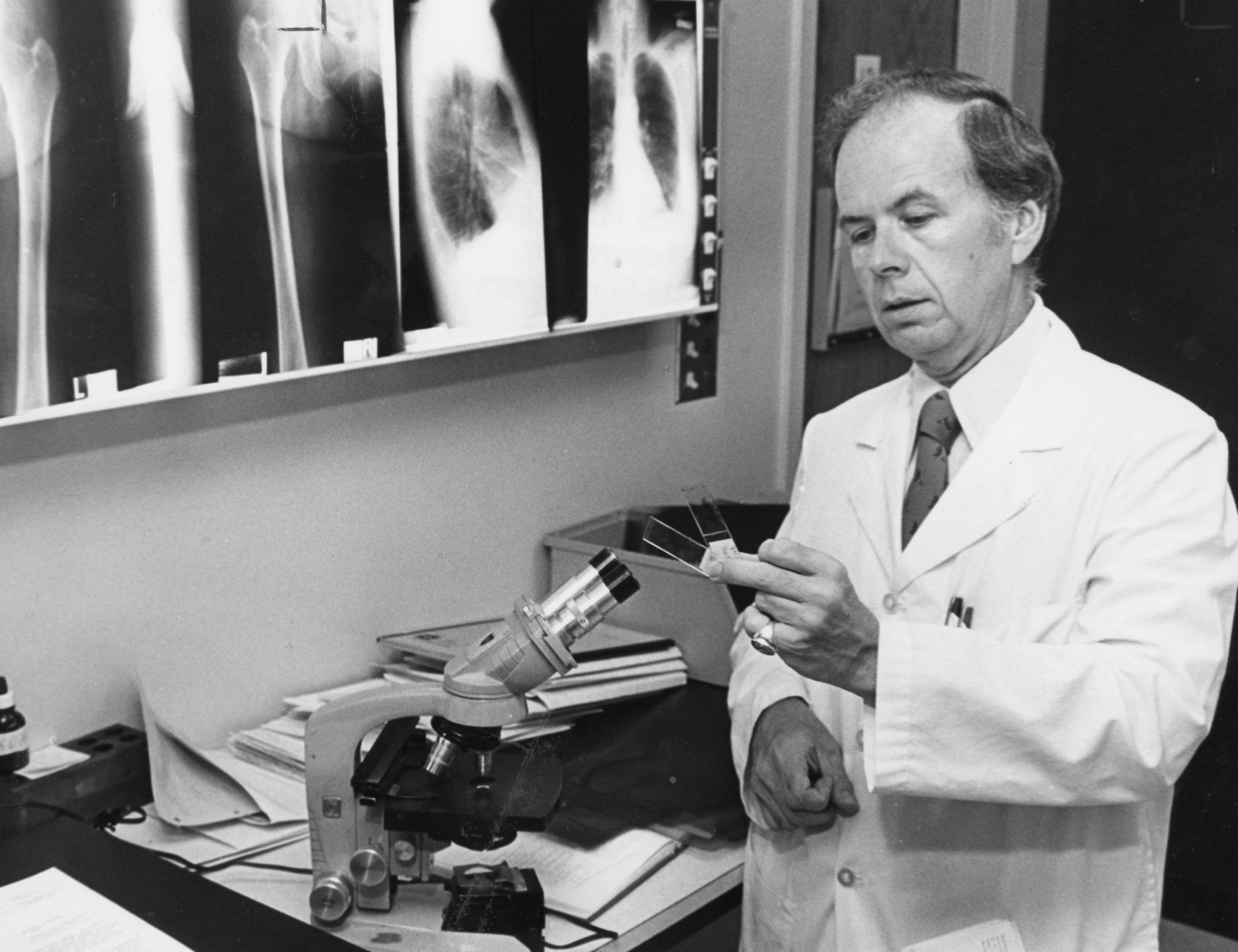

In 1968, Charles B. Hammond, MD, then a clinical associate, founded the Southeastern Regional Trophoblastic Disease Center at Duke, the first center of its kind in the region to combat gestational trophoblastic disease, the development of abnormal cells inside the uterus in the tissues surrounding the fertilized egg that can go on to form cancerous and benign tumors. Using what he learned at the NIH (National Institutes of Health), Duke gynecologists were able to offer patients chemotherapy treatment to prevent the malignant form of the disease from spreading.

Today, this rare disease is considered a curable condition.

“Probably the thing I’m most proud of is, I was lucky enough to go to the National Institutes of Health in the mid-60s at a time when malignancy was being treated that grew from the placenta, or the afterbirth — a universally fatal disease,” noted Hammond, who passed away in February 2021, in a 2011 Duke Medicine (now Duke Health) video chronicling his career highlights. “Someone there had just made a discovery that showed it could be cured with drugs, and while I was there, we refined those drugs; expanded the cure rate to approach 100 percent. The fundamental idea of using drugs in that disease was a radical new one. It had been tried but really hadn’t been proven. And when I was there, we were able to try it on nearly 100 patients … and then expanded to the center here [at Duke]. It transformed a disease, one of the first diseases that was ever cured with chemotherapy. It was a very gratifying time. We didn’t cure everyone, particularly in those early years, and some patients, unfortunately, had complications of the treatment… that’s how we learned.”

The commitment of the Division and Duke Cancer Institute to research and innovation in gynecologic cancers continued throughout the 20th century and entered a new era of discovery in the 21st century.

From individualized treatment, including targeted therapies and immunotherapy; to lifesaving surgical procedures and clinical trial opportunities across disciplines for patients who otherwise would not have treatment options available; to the burgeoning field of onco-fertility (fertility preservation options for cancer patients); treating gynecological cancers has come a long way.

Importantly, as a multitude of treatment options have become available, there’s been a greater focus on quality, safety, affordability, and improved provider-patient communication around treatment goals and quality of life.

And gynecologic oncology faculty have also made global inroads in gynecological care and research — establishing partnerships in more than 10 countries across four continents.

Q & A with Andrew Berchuck, MD

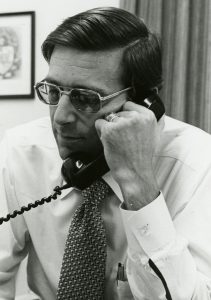

In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Duke Cancer Institute and the 50th anniversary of the Division of Gynecologic Oncology, we asked the third and current division chief, Andrew Berchuck, MD, to elaborate on some of the milestone discoveries at Duke in the gynecological cancer field (including his own) and where the field is headed.

The James M. Ingram Distinguished Professor of Gynecologic Oncology and director of the DCI Gynecologic Cancer Disease Group joined the Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center (now DCI) in July 1987. Since day one he’s led a research program focused on the molecular-genetic alterations involved in the malignant transformation of the ovarian and endometrial epithelium and has published more than 300 peer-reviewed papers in this subject area. He maintains a clinical practice in surgical and medication management of individuals with ovarian, endometrial, and lower genital tract cancers.

Which discovery worldwide, over the past 50 years, has been the biggest game-changer in the field of gynecological oncology?

There have been a number of spectacular advances in the past 50 years that have had a dramatic impact on the field.

Perhaps the most significant has been the development of cervical cancer screening and the HPV vaccine, which almost completely prevents the development of cervical cancer.

In the U.S. and other developed countries, this has reduced cervical cancer death rates by over 90%. Sadly, implementation of screening and prevention in low-resource countries has lagged due to a lack of healthcare resources and cervical cancer remains a leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide.

Can you elaborate on the significance of having identified the role of overexpression and mutation of the TP53 gene in epithelial ovarian cancer? What has that meant for treatment?

In 1991, we demonstrated that mutations in the TP53 gene were frequent in ovarian cancers. This gene is a tumor suppressor that normally prevents inappropriate growth and cancer formation. It was subsequently shown that mutations in this gene are an early event in the development of these cancers that are found in precancerous lesions. Thus far, however, drugs that target this gene have not been successfully developed, perhaps because the protein encoded by this gene resides deep inside the nucleus of the cell.

You were part of a research group that in 1994 discovered the cancer-causing potential of an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 gene in ovarian and breast cancers. What was your role in this discovery?

In the early 1990s, we were collaborating with other research groups in the RTP (Research Triangle Park) area on studies that sought to identify hereditary gene mutations that increase the risk of ovarian cancer. Among these was a group at NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) in RTP that was ultimately involved in the identification of the BRCA1 gene, and a number of Duke tumor-tissue samples were used in this work. It was shown that women who inherit mutations in the BRCA1 gene have about a 40% risk of ovarian cancer and an 80% risk of breast cancer.

Along with Dr. Kelly Marcom, I was involved in the clinical implementation of genetic testing for BRCA1, and later a second breast/ovarian cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2. This enabled the identification of high-risk women who were candidates for risk-reducing surgery and other prevention strategies. Over the past nearly 30 years, I have performed surgery on many women found to have these mutations. On average, about one cancer death is prevented for every three who undergo risk-reducing surgical removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes after completing childbearing.

You were a member of the Cancer Genome Atlas Ovarian Cancer Working group that in 2011 published the first comprehensive genomic analysis of ovarian cancer. Explain the significance of this feat.

When I started at Duke 35 years ago it was the dawn of a new era in which the tools to study cancer cells at a molecular level were first being developed. There was hope that the discovery of the underlying molecular alterations that cause cancers would provide opportunities for new approaches to early diagnosis, treatment, to prevention. This culminated in the federally funded and led Cancer Genome Atlas Project, in which several hundred of each of the most common types of cancers were subjected to comprehensive molecular analysis.

Duke contributed a large number of cases to the endometrial and ovarian cancer analyses, and I had the opportunity to serve on the working group that was involved in analyzing and publishing this data. It was shown that the specific mutations that cause cancer vary between types of cancers (eg. uterine versus ovarian cancer), as well as within a given type of cancer.

This led to a molecular classification system that is now used in many cancer types to direct the use of biological therapies (also known as targeted therapies), including the use of PARP inhibitor drugs in ovarian cancer.

Can you highlight some examples of the role your division has played in surgical advances?

Surgery is a frequently used treatment modality that can cure many cervical, ovarian, and endometrial cancers before they have spread. For much of my career, this involved open surgery with incisions that extended from the pubic symphysis to the navel or higher. This required several days of hospitalization and significant potential for complications and disability.

The development of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in which only a few tiny incisions are used has had an incredibly positive impact on surgical outcomes. Most patients go home the same day. Recovery and disability are dramatically reduced, and cosmetic results are superior.

Duke was an early adopter in implementing both laparoscopic and robotic MIS. Dr. Leah McNally in our group is also involved in MIS surgical trials. Next month, Dr. Emma Rossi, a renowned gynecologic oncology surgeon specializing in robotic surgery, is joining our group in October and will lead further advances as MIS continues to evolve.

Since the mid-1980s, one Duke OB-GYN resident a year out of seven has pursued gynecologic oncology fellowship training. That’s compared to about 1 in 70 nationally. Why do so many OB-GYN residents at Duke choose to pursue oncology?

The Duke Gynecologic Oncology fellowship is a three-year program and includes a dedicated research year. We develop very close relationships with the fellows due to a shared experience in caring for our patients and in working together on research projects. Many have gone on to become faculty members at Duke and other academic institutions.

Working with the Duke residents and fellows has been a highlight of my time at Duke. The large number of Duke residents who choose oncology reflects the intense experiences they have with our service in caring for women with gynecologic cancers. This includes curing many patients with surgery, as well as being involved in multidisciplinary care in which we administer chemotherapy for metastatic disease and work closely with radiation oncologists.

We also care for women through end-of-life when effective treatment is no longer possible. It is striking how many residents applying for fellowship now cite the opportunity to be involved in moments of crisis with patients and families!

Does the work of your former mentees, many of whom are now accomplished faculty and physicians, give you any clues about how gynecological cancer care will evolve as DCI enters the next 50 years of care and research?

There have been many advances in the treatment and prevention of gynecologic cancers. However, disparities in access to the most effective care exist both globally and in the U.S., and this is a major barrier to achieving the best possible outcomes.

Lack of cervical screening in developing countries as well as the lack of infrastructure and personnel to treat cancer remain a reality. Dr. Megan Huchko and Dr. Nimmi Ramanujam have led efforts (a “Revolution Against Cervical Cancer”), including in Peru and Kenya, to address barriers to early detection and screening with education, cultural awareness, and Duke-developed clinical tools. Dr. Paula Lee, formerly in our division, helped build a fellowship in Uganda and now patients there receive care from well-trained oncologists.

In the U.S., many women of low socioeconomic status are uninsured and do not receive guideline-compliant treatment. A recent report by the American Cancer Society showed that endometrial cancer mortality has increased over the past several years, particularly in African American women.

Dr. Haley Moss (’16 -‘19 Duke OB-GYN GynOnc fellow) in our division has been involved in work seeking to understand challenges related to the implementation of gynecologic oncology care, including screening, cost of care, and the impact of the Affordable Care Act on access to cancer services. In 2021, she was appointed founding director of a national VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs) program in women’s cancers.

A significant development that is easy to pass over has been the development of treatment guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Duke was one of the founding members of the NCCN and these widely available guidelines provide an evidence-based approach to treatment. Several members of our group are involved in the various guidelines committees.

In addition to the development of treatment guidelines, there has been a movement to institute quality improvement programs in which the results of patient care are tracked and analyzed. This provides the opportunity to introduce changes that reduce infections, development of blood clots in major veins, would-be infections, and other complications. Dr. Laura Havrilesky (’95-‘99 Duke OB-GYN resident and ’99-‘02 GynOnc fellow) is a nationally recognized leader in this area.

One legacy I hope to leave behind is a program in perpetuity that will allow our former trainees to return to Duke to share experiences and perspectives.

The above special feature was originally published on the Duke Cancer Institute Blog on September 17, 2022.