Excerpted from the The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society’s online exhibition, “Coronation, Cigarette Companies, and Cancer.”

Coronations, Cigarette Companies, and Cancer

“Have you not reason then to bee ashamed, and to forbeare this filthie noveltie, so basely grounded, so foolishly received and so grossely mistaken in the right use thereof? In your abuse thereof sinning against God, harming your selves both in persons and goods, and raking also thereby the markes and notes of vanitie upon you: by the custome thereof making your selves to be wondered at by all forraine civil Nations, and by all strangers that come among you, to be scorned and contemned. A custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, dangerous to the Lungs, and in the blacke stinking fume thereof, neerest resembling the horrible Stigian smoke of the pit that is bottomelesse…” — King James I of England in 1604, A Counterblaste to Tobacco

Written by King James I of England in 1604, A Counterblaste to Tobacco is one of the earliest diatribes against smoking. In it he decries having to breathe in other people’s smoke, rails against its stench, and warns of the dangers to the lungs.

James’s disdain for the noxious plant led him to levy a heavy excise tax on tobacco brought from North America, but 20 years later the ever-increasing demand for tobacco led him to do an about-face and create a royal monopoly for the crop.

Over the ensuing three centuries, tobacco would be a mainstay of the British economy, and Great Britain would be the leading tobacco merchant to the world.

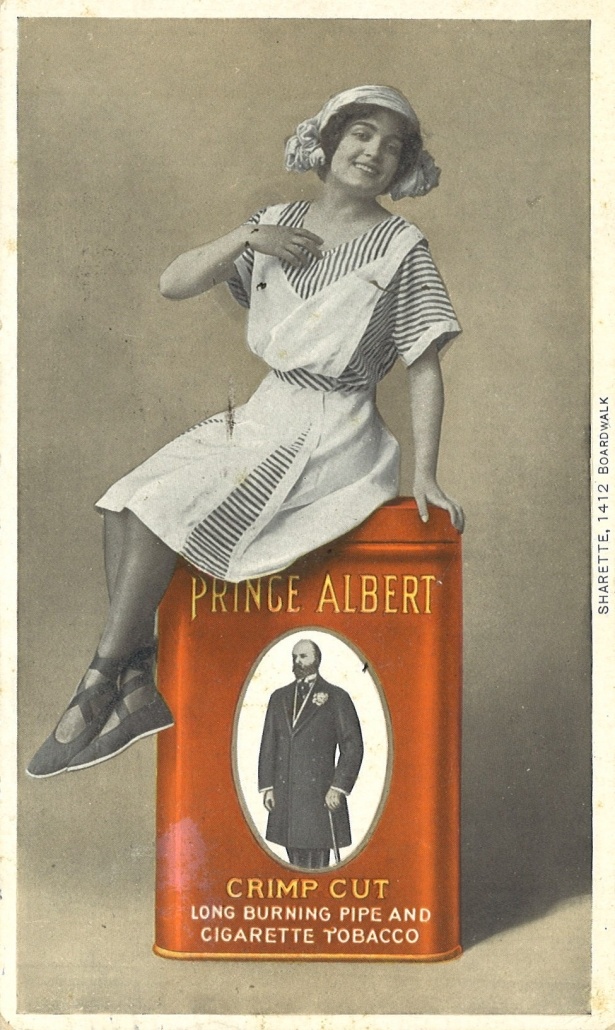

In 1877 possibly by appealing to the love of smoking by Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort, and creating a brand of pipe mixture named for him, tobacco manufacturer Gallaher Limited was permitted to include the coat of arms of British monarchs on its cigarette packages.

Over the next century, cigarette makers used every opportunity to associate themselves and their products with luxury… and royalty. During World War I, when cigarettes usurped cigars as the tobacco product of choice by young men, members of the royal family lent their name and image to the distribution of cigarettes to the boys in the trenches and wounded soldiers in hospitals.

In 1937, Imperial Tobacco, maker of the most popular brand of cigarettes, Player’s, issued an album of tobacco trading cards—a popular hobby among boys—to commemorate the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

To honor Queen Elizabeth II at her coronation in 1953, TOBACCO, the leading journal of the trade, published A History of Smoking from Elizabeth I to Elizabeth II.

To burnish their nicotine-stained image throughout the latter half of the 20th century and beyond, British cigarette companies became patrons of the arts and universities, as well as major sponsors of televised sporting events. During Prince Charles’ and Princess Diana’s visit to Australia in 1983, Gallaher tied one of its cigarettes brands to the royal family in an infamous souvenir front page of The Sydney Morning Herald that featured an advertisement for Benson & Hedges. The previous year, the South-African based cigarette company Rothmanns also tied its Dunhill cigarette brand to an international showjumping event “to be held in the presence of His Royal Highness, the Duke of Edinburgh.”

Consider the devastating reality of smoking not just on the nation—cigarettes are still the leading preventable cause of death in Great Britain in 2023, killing 76,000 a year—but also on the royal family: Queen Elizabeth’s father, George VI, was just 52 when he died from lung cancer. His father, George V, and grandfather, Edward VII, also died of smoking-related diseases, as did his granduncle Edward VIII, the Duke of Windsor. Queen Elizabeth’s sister, Princess Margaret, who smoked heavily, died at 71 from severe lung and heart disease.

Doubtless mindful of the devastating toll taken by smoking on his own family, Prince Charles became an outspoken anti-smoking advocate. In 1982, when I edited the Medical Journal of Australia (MJA) and produced the first theme issue on smoking at any medical journal, Prince Charles was the president of the British Medical Association and the patron of the MJA. Charles is believed to have been responsible for revoking the royal warrant to Gallaher in 1998. He is also said to have urged other close family members to stop smoking.

The positive example King Charles III has set may prove to be the death knell for British cigarette makers, even as they reinvent themselves as veritable pharmaceutical companies and try to entice their nicotine-addicted consumers–plus a new generation of pleasure-seekers–to take up vaping. In this gambit, British American Tobacco and other nicotine pushers (notably the US giants Philip Morris International [PMI] and Altria) are hiring former government health officials (including from the World Health Organization), public health school researchers, and executives of health foundations to endorse their vape products and to mock anyone who does not agree with this “harm reduction” pathway to a “smoke-free world.”

Although PMI claims it wants to transition entirely away from cigarettes, we’ve heard this going-out-of-business sale many times before with each new claim of a safer cigarette. Meanwhile, nearly 90% of the company’s profits still come from the sales of cigarettes, not vaping devices.

The public would be wise to follow the example of Charles III by not having anything to do with tobacco companies or their new products. God save the King.

Click here to view the full exhibition on The Center for the Study of Tobacco and Society’s website.