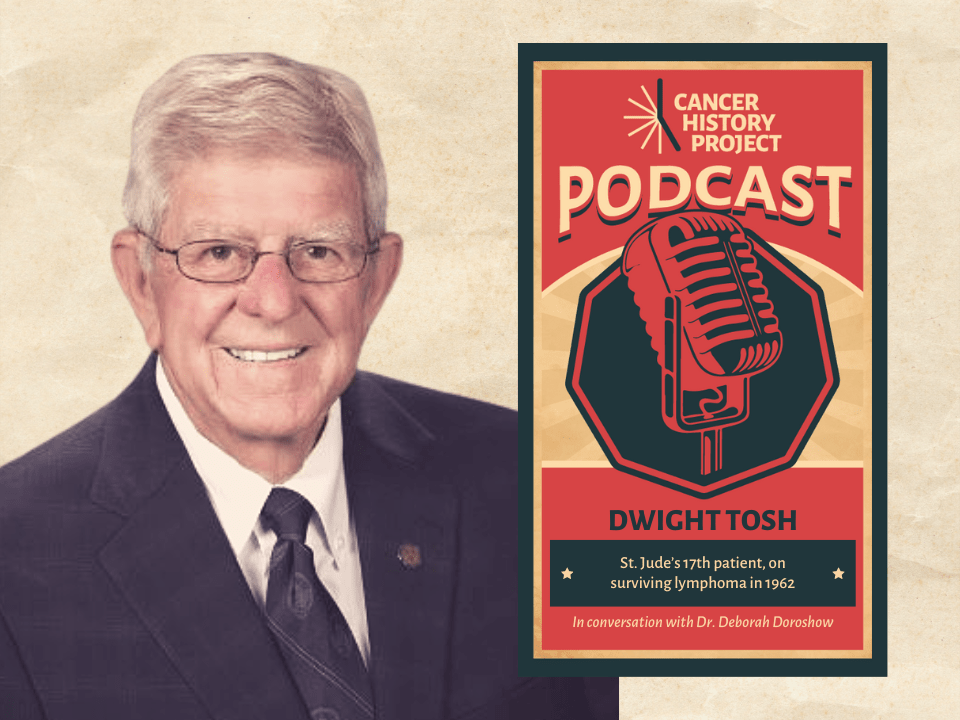

This is the fourth installment of the Cancer History Project’s series of oral histories with survivors of cancer.

The interviews are conducted by Deborah Doroshow, assistant professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at the Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who is also a historian of medicine and a member of the Cancer History Project editorial board.

Dwight Tosh had grown so weak that he was unable to walk. Still, doctors at the rural Arkansas hospital—where he lay in bed for weeks in 1962—were unable to diagnose him.

“My athletic body had been reduced to just a shell of an individual, looked like you’d just taken the skin and stretched it over my bones, just wasn’t much left of me,” Tosh, 73, a Republican state representative in Arkansas, said to Doroshow. “And still, the doctors couldn’t figure out or diagnose what the problem was.”

Tosh, only 13 at the time, wasn’t getting any better. He was running fevers of 107 and 108, and there didn’t seem to be a solution.

“And then a huge knot came up on my neck and a biopsy of that night revealed that I had Hodgkins’s lymphoma,” he said.

Doctors told his family he had two weeks left to live, but Tosh and his parents never quite believed that.

“I still kept the spirit that I’m going to make this,” he said. “My mom and dad, I know they had to be extremely worried, but I saw they took on a spirit as well, that they were not going to let this cancer take their son. And I’m telling you, I remember that. And I drew from it.”

The day after doctors told Tosh’s family to prepare for the worst, he was transported by ambulance through the doors of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. He was assigned a patient number—17.

There, Tosh received an aggressive form of chemotherapy and radiation treatment under the care of Donald Pinkel, the first director of St. Jude.

“It was just devastating,” he said. “I started losing my hair and I just lost my appetite, and of course, I was still running a high grade fever.”

Tosh recalls taking several ice baths at St. Jude, as doctors were desperate to alleviate his fever.

“The fever was just destroying me,” Tosh said. “I’d been running this fever for so long now and never really got a break from it. They were trying everything, but then with a high dosage of radiation and chemo…my body was just almost getting to the point that, like I said, I just didn’t want to do anything, just trying to survive.”

He credits the staff of St. Jude, who he recalls being upbeat, with keeping his morale up—“If I had sensed in them that they were giving up, I probably would’ve gave up too.”

A former athlete, his days of playing on his school’s basketball and baseball teams were now over. He had lost touch with friends from back home, and grew close with fellow patients.

“There were not that many of us there in that wing of that old hospital,” he said. “There’s a bond that develops. You leave all your other friends behind. I’d been out of school for some time. These were my new friends in life and we hung out together, we’d visit. We would just share conversations with each other and their parents and my mom would become good friends.”

Some days, Tosh asked his mother to walk him around the hospital in a wheelchair. He liked to visit his friends that way.

“I’d go by one of their rooms to see my friend. They would be gone and I was just… All their things were gone. Their beds were made,” he said. And I said, ‘Mom, where did they go?’ And she would try to explain to me about death, but I was a kid, I had a difficult time understanding about death and why my new friends were dying.”

Eventually, his fever broke. Doctors declared his cancer was in remission. It was time for Tosh to return to Jonesboro Arkansas and Valley View High School—but not without complications.

“I had lost the arches of both my feet,” he said. “Those muscles had deteriorated to the point that, like I said, I couldn’t walk.”

Tosh may have once envisioned himself trying out for the high school basketball team, but now he faced the challenge of physical therapy. Doctors tasked him with different exercises in which he picked marbles up with his toes, strengthening the muscles in his feet.

“Even today I still have trouble,” he said. “I’ve always bounced, well, I guess I might say I walk on my toes. I’ve always compensated for that.”

In gaining his health back, Tosh’s parents turned to a surprising source of nutrition: pecans.

“My mom had some friends that had a grocery store and they would buy these pecans in these cans by the cases,” Tosh said. “I never got so sick of pecans in all my life, but I was eating those things just nonstop. Then I started gaining some weight. I’d started to be able to walk again, I’d started to recover.”

Though Tosh wasn’t quite ready to get back to competitive sports, he was determined to return to high school and the friends he had left behind.

The only problem? Some of the families in the Valley View community feared his cancer was contagious.

“Some of them even were pretty bold about it. They just said, ‘Hey, if he comes back to school, we’re taking our kids out,’” Tosh said. “I made a promise that I was going to return to school, and I was going to prove to these concerned parents that didn’t think that I should be around their kids, that I was going to prove that just because you’ve been a patient at St. Jude Hospital does not make you any less of an individual.”

Tosh is the first patient at St. Jude to become a 60 year survivor. He spoke recently at the 60th anniversary celebration of the hospital, where he also shared his story.

He’s still living with the side effects of his cancer today, especially after having been treated with such an aggressive chemotherapy and radiation regimen. He’s participated in several studies on the long term effects of childhood cancer treatment, and doctors have begun to help him connect the dots.

“I started having pulmonary heart issues, a disease, when I was in my late forties, and had to have a bypass when I was 48 years of age,” he said. “I developed diabetes, and it’s just, I’ve had to have a hip replacement, and my joints and everything. It just seems like they’re wearing out a lot quicker than everybody else’s.

Tosh maintains the upbeat disposition he had during his time at St. Jude.

“At least I’m still here,” he said. “Though there may be some aches and pains and some health issues that I may not have had to deal with if I hadn’t gotten sick, but I did. And it’s just part of life’s journey.

A recording of the conversation between Deborah Doroshow and Dwight Tosh is available above.

Transcript

Dwight Tosh: Well, I’m 73 years of age and I live in Jonesboro, Arkansas. I’m married and married my high school sweetheart, and we have two children. Our daughter is an attorney at law in Nashville, Tennessee, and my son, he followed in my footsteps and he’s a lieutenant over the Criminal Investigation Division here in Arkansas with the Arkansas State Police. And we have four beautiful and wonderful and healthy grandchildren. That’s just a quick snapshot of where I’m currently at today.

DT: I retired after 37 years with the Arkansas State Police, and I retired from that agency as a true commander with Arkansas State Police. After I was retired several years, I decided that there was just such a void, I just missed being able to help people. I’d spent my whole life in a position to be able to do that. And so I decided to get into politics. In 2014 I ran for state representative here in Arkansas and I got elected and was sworn in, January of 2015. And I currently serve as a state representative here in the general assembly in Arkansas.

DT: Well, when I was 13 years of age, I attended a rural school just south of Jonesboro, called Valley View. And I was an athlete. I was the starter on my basketball team. I was a catcher on my baseball team. I had a great family life. I was healthy and I thought it would last forever. And then I became critically ill. It started out, I just had this rash come up on me and then I started running a fever and then they admitted me to the hospital and I lay in a hospital bed here in my hometown of Jonesboro for weeks and weeks and weeks running just around the clock, a high grade fever sometimes peaking at 107 and even 108.

The infection was just unbelievable, but the doctors were unable to diagnose what was wrong with me. And I was just progressively getting worse, weaker by the day until I finally reached the point that—I had lost my ability to even stand on my own. I couldn’t even walk. And what was once really what I felt like, really my athletic body had been reduced to just a shell of an individual, looked like you’d just taken the skin and stretched it over my bones, just wasn’t much left of me. And still, the doctors couldn’t figure out or diagnose what the problem was. And then a huge knot came up on my neck and a biopsy of that night revealed that I had Hodgkin’s lymphoma. And of course the doctors started treatment for the cancer.

The body was already so weak that the treatment was unsuccessful, and I just wasn’t getting any better. Finally, it reached the point where the doctors felt compelled to meet with my parents, and told them—basically what they told them was, is that all that they knew to do had been done and told my parents that they needed to prepare for the worst. Of course, I’m told that my mom asked the question, “Well how long does my son have?” And of course a doctor said, “Ms. Tosh, there’s no way we can know for sure, but unless something turns in our favor, unless we get a break, but if things continue like they are, he really can’t last much longer,” and they said “Maybe two weeks, we can’t say for sure, but it’ll be a miracle if he goes past that.”

DT: Well, the doctors came in with my parents and told me, and that’s how they broke the news to me that the biopsy, came back that I had the Hodgkin’s lymphoma and that they were going to start treatment for that. To my knowledge though, at the local hospital, I just don’t recall ever receiving any radiation or chemo at the local hospital.

I don’t think I did. I don’t remember that because it seemed like after they finally was able to diagnose what I had, the cancer, that it was just shortly after that, that the word came about. It was the next day after the doctors had told my parents that they didn’t know what else to do.

Keep in mind now, this is in 1962. This is a local hospital and what was somewhat of a small town at that time. Probably every doctor in town was trying to figure out what was wrong with me to come up with some type of treatment plan.

But the very next day after doctors told my parents to prepare for the worst, I don’t know, but from somewhere, from somehow, from someone, word came about a new research hospital that had just opened its doors in Memphis, Tennessee, St. Jude. And so that very next day I was transported by ambulance from my local hospital here and carried through the doors of St. Jude.

DT: It was devastating. I knew I was extremely sick and I just was fighting as hard as I knew how to fight. Up until that point, I just kept thinking, I’ll get better. And then when I got the diagnosis of the cancer, I still kept the spirit that I’m going to make this. My mom and dad, I know they had to be extremely worried, but I saw they took on a spirit as well, that they were not going to let this cancer take their son. And I’m telling you, I remember that. And I drew from it.

I just kept thinking, I’d be able to recover. I’d be able to go back to school. And I love basketball more than any sport. Here I was in eighth grade—I was a starter in eighth grade on my basketball team. And I was a pretty popular kid. I kept thinking I’d be able to go back to that. Of course, that was something that was taken away from me because of the cancer. I never was able to do that. That’s something that, it’s always bothered me because I try not to live a life of what if, because I think I’m blessed to have lived the life that I’ve been able to live, but what if? Like I said, I didn’t choose to be sick and if I could have changed it, I would, but I couldn’t, it was the hand I was dealt.

And so you live life to make the best of it, but that was one of the hardest things, is when I finally realized that I would never be able to return to school and live the kind of life that I was used to, playing sports and being that kid on campus that was so popular, and that’s another story because when I did return to school, that’s getting ahead of ourselves, but we can discuss that later, but I encountered a lot of rejection and I’ll share that with you later on in the interview.

DT: Well, my parents, later on in life, they didn’t share that with me until I was… It was several years later on when they told me. At that time, that was not something they would’ve ever shared with me at that moment, because they was trying to keep my spirits up and trying to keep me in that fighting mode that we can beat this and they didn’t want me to know that people were starting to give up, that the doctor said then was inside, unless something changed to our benefit.

That kept me fighting and thinking there was still hope, but it was later on that my parents shared that story with me, and what my mom had actually asked the doctors during that meeting.

I was taken by ambulance over from—the very next day after, they transferred me and on April the 23rd, 1962, I was carried through the doors of St. Jude and I was assigned a patient number, 17. At St. Jude, if you’re not familiar with it, what they do, they assign you a patient number in the order that you’re admitted as a patient and that number’s yours, it’s yours forever.

They will never reuse that number regardless of the outcome for the patient. It’s never used again. So I was the 17th patient that was admitted to St. Jude. And just to give you an example, St. Jude, I was told the other day that a child being admitted there today, their patient number would be somewhere around 80,000.

I was the 17th patient, and of course the doors at St. Jude had only been open for a short time. I spoke over there a few weeks ago at the 60th anniversary celebration, and they recognized me as being the first 60-year survivor from St. Jude. As I told the board of directors, and Marlo Thomas that day, I spoke to a large group.

I just said, if 60 years ago I lay in a hospital bed just a few hundred yards for where I’m standing today and laying there lifeless, just almost lifeless, trying to cling to life, if someone had walked in my room and said, “Dwight, there’s something we want you to know, that 60 years from today, you will return to St. Jude and your story will be told, and you’ll be recognized as the first 60 years survivor from St. Jude hospital.”

I said, I really doubt if anyone in that room 60 years ago today would have believed that this day would have ever occurred. Other than that, my mom might have believed it, but I wouldn’t have believed it. I don’t think any of the doctors really would have, because at that time, it was just, I was seeing my new friends.

There were not that many of us there in that wing of that old hospital. I got to know all of them. Those were my new friends in life. And one day I’d ask my mom to take me around. And so I’d get a wheelchair to visit with them and I’d go by one of their rooms to see my friend.

They would be gone and I was just… All their things were gone. Their beds were made. And I said, “Mom, where did they go?” And she would try to explain to me about death, but I was a kid, I had a difficult time understanding about death and why my new friends were dying, but that’s when, like I said, I still have different memories of my time at St. Jude.

DT: You know, we just all knew we was in the same battle, we were all fighting a different type of cancer. Most of them, I wasn’t sure what they had. I knew they were like me, they were there, they were extremely sick like myself, had a catastrophic illness, and we just bonded together. There is a bond that once you’re a patient, and I can only speak for my time at St. Jude, I hope this occurs elsewhere, other places or not, but there’s a bond that develops. You leave all your other friends behind. I’d been out of school for some time. These were my new friends in life and we hung out together, we’d visit. We would just share conversations with each other and their parents and my mom would become good friends.

I can even remember a time when they gathered all of us up there in this big open room, on the wing of where all the patients were kept. Now, back in 1962, we were all kept in isolation in that one wing, we were not allowed to leave that wing. No one from the outside world was allowed on that wing other than our parents. It was a research hospital and it was still the unknown.

Today, you see patients moving all about the hospital while I’m over there, but in ‘62 things were different. Anyways, I remember on one occasion, a nurse came in, she said, “We got some special guests coming today.” And I said, “Who?” And The Three Stooges came to see us. And they gathered us up. Like I said, there was wasn’t many of us there, I was the 17th patient. They took us to this big open room in the middle of that wing of the hospital.

And I remember they entertained us and we laughed. I think back, and it was such an enjoyable time, just, they made us forget for a little while. They made us forget just how sick we really were. Like I said, it was hard on me, when one of my new friends, when I looked up and they were gone and I just couldn’t understand, I had such a hard time dealing with that.

DT: She never left my side. See, today at St. Jude, you’ve got, oh my goodness, got the Ronald McDonald House, the Grizzly House, Kay’s cafeteria, the list goes on. But back in 1962, they brought a recliner in and they put it in my room, and my room was my mom’s room. She never left my side. She was never out of my sight. She stayed with me. She was right there with me. My dad, obviously, I had siblings, I had two brothers and a sister, and he’s back here working at a couple of jobs and trying to pay off the astronomical bills that had been accumulated while we were at the local hospital. Of course at St. Jude, that part of the burden was severed when we arrived there. But she never left my side.

DT: Yes. Dad would come over and of course he was allowed on the wing of the hospital where I was kept there. Now my brothers and sisters, and even other family members and friends. They had this room. It was an empty room that had a window that looked out into the parking lot.

And of course they would come up on the outside there, that room at the hospital. We would try to visit and communicate through the closed window, obviously. And I just remember they would stand there and I would try to talk to them and we would just back, forth the best we could. I remember when they left, I would stay right there at that window until I watched them get in the car and drive off. I still remember that feeling, because it was so sad, because I just wanted to go with them and I couldn’t, but that was the only way that I could see them. They were not allowed in the patient area.

DT: I think my parents did. I know that doctors from St. Jude today, the ones that are there today, obviously have looked at my medical history and the type of treatment that I’ve received. Matter of fact, I’ve been back to St. Jude, well, on many occasions, but I’ve actually been back over there for three life studies. I was the first patient they brought back for a life study program. They put me through a barrage of tests just looking, trying to find how cancer, maybe later on in life, some of the issues that I’ve had, how’s it related to my childhood cancer and so forth. I remember they were going to do I believe it was a spinal tap on me. I remember my mom, I remember hearing part of that conversation and she was somewhat reluctant.

I remember they talked to me about it and I said, “Hey, if it’ll help me to get better, let’s do it.” My mom finally gave in, but I remember she was little bit reluctant to, for whatever reasons. I never understood that, but something really concerned her, but I know that doctors, obviously not the doctors that were there when I was being treated.

When I went back over for the life studies, I know the doctors had met with and told me that they looked at and they said there is just no way that if we were treating someone with the same cancer, that we would give them that high dosage of chemo. Apparently it was real aggressive treatment, but I didn’t know that at the time, obviously I really wasn’t involved in those conversations.

My mom was, but they never shared that with me. But doctors have told me, they said that it was really an aggressive type of treatment. It was a strong, strong dosage of chemo, radiation and chemotherapy, or chemo. That probably weakened me quite a bit, even more. I lost all my hair and went through all of that, but whatever it was, I was back over for the life study and they were looking at everything. Something worked.

DT: Oh, it was just devastating. I started losing my hair and I just lost my appetite, and of course, I was still running a high grade fever. I remember them coming in, and they would take me in and put me in a bathtub and just pour ice. I’m just laying there in that tub covered with ice, about to freeze to death. It was so cold. They were trying to get that fever down. That was in 1962.

I don’t know what they would do today, but in 1962, that was the method they used, trying to get the fever because the fever was just destroying me. I’d been running this fever for so long now and never really got a break from it. They were trying everything, but then with a high dosage of radiation and chemo, and like I said, my body was just almost getting to the point that, like I said, I just didn’t want to do anything, just trying to survive.

DT: You mean talking about in 1962?

DT: No, I do not. I have no idea. I think St. Jude had just opened its doors, and I don’t think. I’ve never heard that. I’ve never been told I was. They brought me in, it was research and I think they were just trying to find the answer to the problem. They were trying different things. Like I said, high dosage of radiation and chemo and the spinal tap and other things, I can’t remember what all.

It was just nonstop, but I don’t think there was any type of any clinical trial at all. I think, like I said, they had several delays in opening the doors at St. Jude, and they were able to overcome those. Like I always say, thank goodness, there wasn’t one more delay because the opening of the doors at St. Jude and my survival were critical. And so I’m glad there were no additional delays because.

DT: Things might have turned out differently. I’m not sure you need this or not, but while I was there, Danny Thomas came by one day after the Three Stooges had been there and same nurse came in and said, “You got a special guest coming today,” and I’m telling you, Debbie, I got excited. I thought, wow, Three Stooges. And I said, “Who?” And she said, “Danny Thomas.” And I didn’t say anything, but I remember thinking, “Who’s Danny Thomas?”

I was just a boy from the rural—a country boy, I really was. I went to a rural school and I didn’t keep up with that. I noticed that when the nurse left, I saw my mom get up and she started brushing her hair and putting on base [makeup] and stuff.

She was dolling up, and I remember I asked her, I said, “Mom, what are you doing?” I’m laying there, I said, “What are you doing?” And that was really unusual for her I thought. She said, “Son, Danny Thomas is coming by to see.” And I said “So? Who in the world is Danny Thomas?” And of course she went off how famous he was and known all around the world, famous actor, an icon had his own TV show. She said besides all that, he’s the founder of this hospital. And then, I really didn’t realize how special that time was that I spent with him until later on in life.

When I reflected back on that meeting with Danny Thomas, that’s when I was an adult, and I thought about, there I was, an old boy like me. I was actually in the presence of greatness and in the presence of what I say, the man himself, Mr. Danny Thomas, the founder. I’m just glad he stayed the course and never gave up on his dream until his dream became a reality, because he never gave up on his dream, it’s allowed someone like me to live my dream.

DT: You know, the nurses were just fantastic, and the doctors. I think it was Dr. [Pinkel], I believe. And he was one of the first doctors there. And it was several years ago, and I went over, they had him come up on the big screen and I was there, and we visited a little bit and talked about while I was there, and he remembers treating me. And I remember him.

DT: You’re talking about while I was in the hospital?

DT: You know, the doctors were, the nurses were fantastic, the doctors, and they were constantly keeping us updated, and just everybody was so encouraging. It’s just like, “Hey, we’re making progress, we’re doing this. Things are getting better.” It was always positive. And that kept my hopes up, like I’m going to beat this.

I’ve had people ask me, “Did I ever think that I was not going to make it?” And I never remember having those thoughts. I guess because the people around me, including my parents that I’ve already mentioned, and then the doctors and the nurses, everybody was so upbeat and so encouraging. If I had sensed in them that they were giving up, I probably would’ve gave up too.

But that didn’t happen, and I applaud them, they were good to me. They took good care of me. Talking about my treatment back in 1962, they didn’t do radiation in chemo there at St. Jude. The only time I was allowed to leave that wing of the hospital is when the nurse and them, they’d come in, they’d put me in a wheelchair and the nurse would push me. And my mom would walk right along beside us. And we would go off of that wing and go through an underground tunnel. I still remember that tunnel. I remember it was damp, and it was poorly lit. That nurse would push me and my mom walking beside us. We would go through that tunnel over to an adjoining hospital. I believe it was there at that time, it was called St. Joseph Hospital.

It was there they had to take me to receive my radiation and chemo treatment, of course. I’m sure they administered the dosage that the doctors at St. Jude had called for for me. But anyways, that’s where I had to go. They were all positive, and as a result of that, I stayed positive. And in spite of all that was around me, with death, and just not seeming like I was getting any better.

I kept thinking any day we were going to get this behind us, just hang on, that day’s coming, we’re going to beat this. We’re going to get better. And tomorrow could be that day, that this thing turns around for us. I just never gave up. And I had such a will to live. I just wanted to go back. I just kept thinking in my mind, I kept thinking that I would be able to go back and resume the life that I had before I got sick, And that I’d just go back and pick up where I left off. I think that really kept me going, even though in reality, that wasn’t going to happen, but I didn’t really realize that at the time. That was not in my future to pick back up where I left off.

DT: Yes. After the fever broke, and of course then when the fever breaks, then I started feeling better. The doctor says, “Hey, I think we’ve got this. I think we’ve got the cancer behind us. I think it’s in remission.” And so they watched me for a while. And I started feeling better.

I had lost the arches of both my feet, I guess those muscles had deteriorated to the point that, like I said, I couldn’t walk. And so even after they sent me home what they had me do after I got home, I would sit in a chair there at home, and my mom would lay these marbles, you know what I’m talking about? Those little marbles used to play with as a kid.

DT: And they would lay those little marbles on the floor. My job was to take my toes and try to pick those marbles up. But I guess that was causing me to build the strength up in my ankles, and my arches, and all that. Then I started walking, but I never, ever fully recovered.

Even today I still have trouble. I walk now and after I was able, like I said, I learned how to walk again. I’ve always bounced, well, I guess I might say I walk on my toes. I’ve always compensated for that. People around me never really notice it, it’s not that obvious, but a lot of people walk on their toes.

DT: How long was I? This was several months after I was admitted before I ever got to go home. Then, even after I got to go home, I was going back and forth maybe once or twice a week, and once a week. And they’d say, “You’re doing great, continue on.” I’m trying to think.

I was probably around 16 years of age when they told me I no longer needed to come back unless something redeveloped. And so I was probably about three years from when I first was admitted to St. Jude before they totally just released me, that I didn’t have to go back to see them. But anyway, that recovery was a long time, it took me years to build myself back up, become strong again, and to move on with life, putting my weight back on. It just took a while to recover from the devastation of the cancer.

DT: You’re talking about the recovery part?

DT: Like I said, I’ve got all these exercises with the marbles and then my mom, and I don’t know that I’ve ever shared this with anybody, but my mom had some friends that had a grocery store and they would buy these pecans in these cans by the cases. I would sit around, and I guess those things put weight on you.

I don’t know, back in 1962. I never got so sick of pecans in all my life, but I was eating those things just nonstop. Then I started gaining some weight. I’d started to be able to walk again, I’d started to recover, and then I’d actually go out and I couldn’t go back and play competitive sports again, but I’d go and I’d start dribbling that basketball, and playing and pushing myself, and trying to get back, and kept thinking I’ll be able to get back to play my junior year, my senior year. And those things never happened. The only sport that I was able to return to was my senior year.

I was able to play baseball my senior year, but I never could get back on the basketball court. Now, after I graduated high school, I kept getting stronger and stronger. And eventually I started playing independent basketball in the league and got back to my old self and got where I was a pretty good ball player again. I think things like that really caused me to build my strength back up, to get my body back in the shape that it was before the cancer. And I just, like I said, I just pushed myself to do that.

DT: Not really. And well, a teacher too came by the house and they tried to, they would work with me and try to keep me up to date, but that’s difficult to stay up [to date]. When I was 13, in April, when the school year was getting about over with, I’d missed several weeks before I stayed at St. Jude. Then it was later in the fall, or September, October, somewhere in there of 1962, several months later, St. Jude said that they’d release me to go back to school and I got excited. I couldn’t wait. I just couldn’t wait. I had been away from all these friends.

I hadn’t been around them now, in my goodness, seven, eight, nine months since I’d spent any time with my friends from school that I played ball with, spent the night at their house and they’d be at mine. And I just hadn’t hung out with them.

I was, like I said, trying to recover. I was excited and you have to remember, I attended a rural school and when I got sick, everybody out through the Valley View community, we all knew each other. I was a well known kid and my family, everybody knew us, and so when I got sick, I’m telling you that word spread fast throughout the community. And it spread just as fast throughout the community when they found out they were going to take me to a research hospital in Memphis. Can you imagine, in 1962, what people thought? The rumors were flying.

Once I was released by St. Jude and told I could go back to school, that word traveled just as fast. It was a difficult time because families that had reached out to us, what they could do, and maybe even they took up money to help my parents, our family, during these difficult times, all at once. I remember one night at my house, my dad, mom called me in the living room and somebody sat me down and said, “We need to tell you we’ve gotten a call from the superintendent at the school. Some of the parents are calling the school and the school board members. And they don’t think…” They’re really concerned about me returning to school.

They just didn’t think I should. And some of them even were pretty bold about it. They just said, “Hey, if he comes back to school, we’re taking our kids out.” As my dad said, I got upset, got mad. I said I just couldn’t believe this, I always thought, here it is, love now has turned to rejection. I guess they thought I was contagious.

The unknown scared them, and dad reminded me, that night in the living room. I can’t remember word for word what he said, but he made a profound statement. He said, “Son, don’t be too hard on these folks or these people.” He said, “They love their children, just like we love you. And they’re just trying to protect them like we’re going to protect you. And so if you don’t want to go back to school in that type of environment and where you may receive that type of rejection, then we’ll find another alternative to your education.”

And he started naming off all these things we would do. And I was listening, but really, I wasn’t listening either because I knew that was unacceptable. We couldn’t do that. We couldn’t afford all that. And so he just said, “Hey, the decision is yours. You decide what you want to do. And your mother and I will support you.” And he said, “Think about it. And you let us know tomorrow.” And I said, “Am I going to be allowed to go back to school?” And he said, yes, the superintendent said that the school board had voted. And even though there were a lot of parents concerned, they made the decision that if I wanted to return to school, I would be allowed to.

So I said, “Good.” I said, “Well, in that case, we don’t need to wait till tomorrow.” I said, “I can tell you right now, what I choose to do.” I said, “I choose to go back to school.”

And I made a promise that night in that living room to my parents, I made a promise that I was going to return to school, and I was going to prove to these concerned parents that didn’t think that I should be around their kids, that I was going to prove that just because you’ve been a patient at St. Jude Hospital does not make you any less of an individual.

And I told my parents that night, I said, “I’m going to live the rest of my life to prove that those kids at St Jude Hospital aren’t just some sick child, that they are warriors, that have endured more pain and agony than most people will ever know in a lifetime.”

And I said, “I promise you, mom and dad, that I’m going to live the rest of my life to prove that you can be a patient at St. Jude Hospital, and you can go on and live a full and productive life.” I set out on a mission that night. I was driven by the fact that those people, I’d spent the night at their house. And I was driven to prove that they were wrong. I don’t know what anybody else thinks, but I think I’ve been pretty successful fulfilling that commitment that I made to my parents.

DT: There were some kids that they wouldn’t have anything to do with me. There was some, they actually, the school—if one of the parents said, “Hey, if he’s coming back to school, and just make sure that our child’s not sitting beside him in class.” They would actually find someone that didn’t have a problem with me being back in school and that’s who sat beside me in the class. And I remember those kids, and I thought, wow. Others, they would sit on the other side of the room, but it wasn’t their fault. It was because their parents, not them, it was their parents pushing this. There was that rejection.

And I think one of the things that really, and today is still just, sometimes it’s still hard for me to believe, but I think one of the things that happened, when I traveled across the United States telling my story—a lot of stuff I’ve told you, I don’t ever tell them that story, but that’s fine too. One of the things I always tell, is that one of the real heroes in my life, which was this girl in school, and I’m telling you, she was selected by the student body as the most beautiful girl in school.

She was selected as Miss Valley View, girl with the best personality, the list goes on. While so many people were walking away from me, this girl, this most beautiful girl in school turned, and I’m still amazed today, but turned and walked straight towards me, walked into these arms and we became high school sweethearts.

This past May 30th, we celebrated our 52nd wedding anniversary.

DT: When you’ve got the most beautiful girl in school that takes an interest in you and knows all about your battle with cancer, and she becomes your high school sweetheart, that sends a message.

Other kids have got to be going, “Wow. She likes this guy. Look.” And I still looked pretty rough, I was still pretty thin. I hadn’t made it all the way back yet. When we decided to get married, I don’t know that I’ve ever shared this with very few people, but her mom sat her down and told her, by now, I’m 21 and she’s 21. So she told her, said, “When Dwight was young, he had all that illness and all that treatment he received.” She told my wife, said, “You may not be able to have kids, he may not be able to father children.”

DT: No, that’s what my wife’s mother told her, said, “I want you to make sure that before you marry him, you understand that.” And she said, “Mom, I do. I know that we may never be able to have, I may never be able to have kids. We may not be able to, because of what happened to him, but I love him. And I’m going to marry him regardless.”

But the good Lord blessed us. I was able to, a lot of people that received that radiation and chemo treatment, I’ve talked to some of the parents over there whose kids been through it. Of course, now they can tell them today. Back in the sixties, you didn’t know if you could or couldn’t, but anyways, but we took a chance.

She took a chance on me. We did. We’ve got two awesome kids that I talked to you about earlier and wow, have they both set the world on fire, so successful. Then we have four grandkids, and everybody’s healthy and doing good. So, yes. She’s a real hero, obviously, she could have had probably any boy she wanted in school. And she picked an old boy like me, that was trying to fight back from cancer, and why to this day, I still don’t know, but I’m glad she did.

DT: Yeah, the life study program when I went back, participated in that. I guess the first one I don’t know was10 or 15 years ago. Like I said, I’ve been involved in three of them now. Some of the things—they think that some of the underlying health issues that I have today, from the study, they feel like very well could go back to the treatment that I received, and it shows up later in life.

I started having pulmonary heart issues, a disease, when I was in my late forties, and had to have a bypass when I was 48 years of age. When I was in my early sixties, I developed diabetes, and it’s just, I’ve had to have a hip replacement, and my joints and everything.

It just seems like they’re wearing out a lot quicker than everybody else’s. I’m still going, I am still pretty active and still go hard, but I can sure tell that it just seems like that—and I don’t know if it is—but the doctor seems to think some of that very well could be that’s part of that study program.

It could be from that high dosage of chemo and radiation I received when I was a kid that got long term effects now that are showing up here later in life. That’s part of it. At least I’m still here. Though there may be some aches and pains and some health issues that I may not have had to deal with if I hadn’t gotten sick, but I did. And it’s just part of life’s journey.

DT: No, you did an excellent job. I think, wow, you covered everything. You probably covered more than anybody I’ve ever talked to, about it. Fantastic job. Your questions were spot on. And it really probed my mind and caused me to go back and think it through, a trip back down memory lane with a lot of this stuff that I’ve forgotten about.

DT: Well, I appreciate you and I thank you so much and you let me know if I can ever help you. And if you don’t mind, once you shut the recorder off, I’ve got one last question I’d like to ask you once the recorder goes off.