Originally published in Outlook Magazine, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Spring 1996.

On any Saturday morning in the 1960s and ’70s, more than 100 patients would line a single corridor of Queeny Tower. They had come from all over the world to consult Joseph H. Ogura, M.D., head of the School of Medicine’s Department of Otolaryngology and a legend in his field, whose surgical innovations had forever changed the treatment of laryngeal cancer.

Donald G. Sessions, M.D., professor of otolaryngology and one of a legion of residents trained by Ogura, still sees some of his mentor’s former patients. “They loved and honored him not only because he was able to cure them, but also because he allowed them to have normal speaking function. To them, he was not just a doctor: he was a phenomenon,” he says of Ogura, who died in 1983 at age 67.

One grateful patient was comedian Shecky Green, who bragged on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson about “my St. Louis doctor.” Another was St. Louis businessman Arthur R. Lindburg, who established an endowed professorship which Ogura filled from 1966 until his death.

During a distinguished career spanning nearly 40 years, Ogura did more than improve surgical technique and patient care. He was a prolific researcher who published nearly 300 articles, contributed to some 20 books and delivered more than 100 lectures around the world. His widow, Ruth, who lives in St. Louis, recalls that his staff used to call him “the TWA professor of otolaryngology.”

Ogura also changed the direction of his field by moving it sometimes in the face of strong opposition from his colleagues into territory long claimed by general and plastic surgery. “Now programs around the country are doing this work, but he was a national pioneer in pushing otolaryngology into ever more advanced head and neck surgery,” says Stanley E. Thawley, M.D., associate professor of otolaryngology who also was trained under Ogura.

Much honored for his achievements, Ogura was only the third physician in the history of the American Laryngological Association to receive its coveted “triple crown”: the James Newcomb Award in 1967 for laryngeal research, the Casselberry Award in 1968 for nasopulmonary work, and the DeRoaldes Gold Medal in 1979 for career accomplishment. He belonged to some 30 professional societies, including the prestigious Alpha Omega Alpha; he received medals from India, England, Finland and Yugoslavia. Presidents Nixon and Ford both appointed him to the National Cancer Advisory Board, where he served for eight years.

On the School of Medicine faculty from 1948 until his death, Ogura headed his department from 1966 to 1982. Here, too, he left a lasting mark.

“He built a very strong department, with wonderful faculty and an excellent residency program,” says William H. Danforth, M.D., chairman of the Washington University Board of Trustees. “He gave it an international reputation; in fact, he really helped define what a department of otolaryngology should be.”

“Joe Ogura was the essence of the academic physician; a leader who had the talent, drive, standards and personality to make a lasting positive impact on patient care as a clinical pioneer and as a mentor-teacher,” says William A. Peck, M.D., executive vice chancellor for medical affairs and dean of the School of Medicine.

Ogura may have seen his own most important role as that of teacher. Colleagues picture him proudly leading his close-knit corps of residents and fellows down hospital hallways. As he once put it, “Our true role as teachers, clinicians and investigators is to try to produce people who will surpass us.”

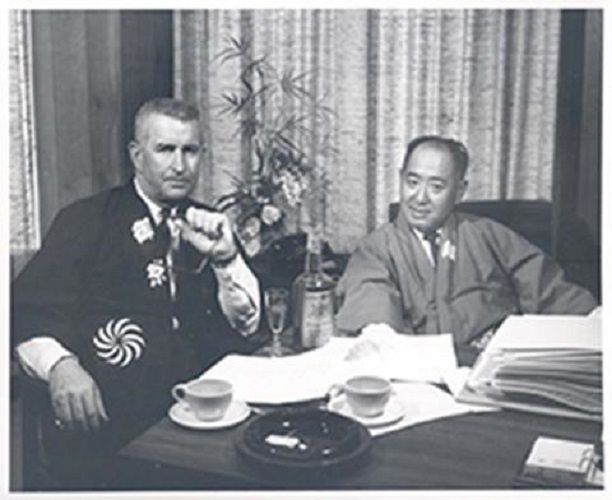

Satoru Takenouchi, M.D., of the Takenouchi E.NT. Clinic in Kyoto, Japan, worked with Ogura as a research fellow from 1963 to 1967. “He was a superior teacher,” he says, “who had the rare ability to stimulate us to achieve our best. He taught us the spirit of challenge and achievement in research work. He was one of the greatest teachers in my life.”

Out of some 27 Japanese otolaryngologists who trained with Ogura, Takenouchi adds, fully half are heads of otolaryngology departments at major medical schools across Japan. Ogura trained doctors, says Takenouchi, “with many valuable papers were highly esteemed at the faculty meetings in which new chairmen of the department were chosen.”

“He raised a generation of physicians that was surgically superb,” says Gershon J. Spector, M.D., who was hired by Ogura as a staff member in 1971 and is now professor of otolaryngology. “They could operate with the best in the country, right away. People were begging for our residents because they needed no prompting; they would take over a unit and within a few years it would be large. They had learned how to do it.”

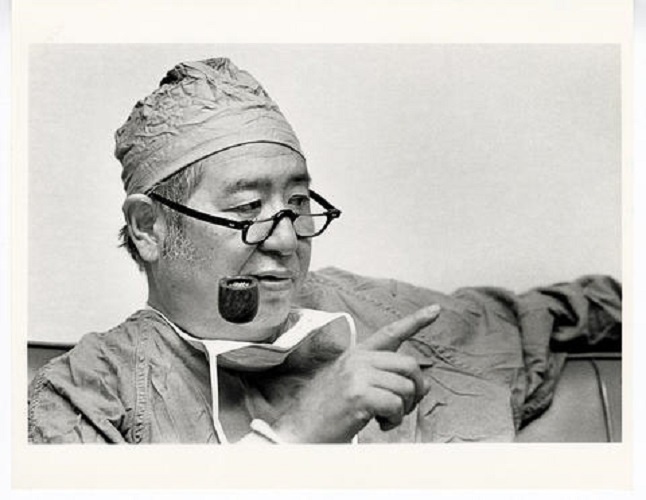

In his personal life, Ogura was a complex and some times contradictory figure. His hallmark, for example, was a worn pipe, which he carried with him constantly. Yet it was empty. With characteristic decisiveness, he had quit smoking cold turkey after a benign spot showed up on one of his lungs.

Driven, Ogura often spent 15-hour days at the hospital. He could be impatient—even brusque—in his manner. At grand rounds on Thursday mornings, he routinely sat next to the light switch in the auditorium. If speakers took longer than planned, Ogura began switching the lights off and on to urge them to shorten their remarks.

Once a student with laryngitis went to the clinic, where Ogura found him and looked at his larynx. “You have laryngitis,” said Ogura, “you’re on voice rest,” and walked out of the room. But the student wanted to know more and ran after him. “Dr. Ogura, does that mean I shouldn’t talk?” Ogura’s reply was brief and to the point: “Shut up.”

But at times he could he gentle and reassuring. If a resident whispered to him that a patient was having problems accepting his illness or that a relative had died, he was the soul of compassion. “When he walked into the room of that patient, you saw a different Dr. Ogura,” says Thawley.

With his students, he may have simply hated to accept mediocre performance . “He set a high standard for them, which most were willing to achieve,” says Hugh Biller, M.D., professor of otolaryngology at Mt. Sinai Medical Center, who recently stepped down after 23 years as department chair.

A kind of father figure to his residents, who called him “the Chief,” he remained loyal to them long after they had left his program. “You were like a member of his family,” adds Thawley. “And it didn’t matter if you were a shining star or a problem kid, you were always part of that family.

Ogura was born in 1915 in San Francisco. Just four years old when his father died, he worked summers in salmon fisheries to put himself through college. He graduated from the University of California – Berkeley in 1937 and received his M.D. from the University of California at San Francisco in 1941.

After Ogura had spent a year as a resident in pathology, war fever struck the West Coast and Japanese-Americans—including some of Ogura’s relatives—were moved to “relocation camps” for internment. Joseph and Ruth Ogura, newly married, had to leave California suddenly; at Cincinnati General Hospital he did a year’s training in pathology, followed by two in internal medicine.

Switching fields a second time, he moved to St. Louis in 1945 where he did a three-year residency in otolaryngology, then joined the School of Medicine faculty. During this time, Ogura’s specialty was undergoing a kind of identity crisis. Its traditional work in ear infections and tonsil problems had decreased with the advent of antibiotics, and it needed a new focus. Ogura and a few colleagues across the country decided the field should expand into head and neck surgery.

Soon he was using brilliant operation-room technique to modify existing surgical procedures and pioneer new ones. In patients with cancer of the larynx, he helped develop partial laryngeal surgery in which he conserved speech by leaving part of one of the two vocal cords intact.

“He was a superior clinician, an extremely astute diagnostician and a superb technical surgeon who knew the physiology of the larynx and the upper airway as well as any basic scientist alive,” says Biller.

Three days a week were reserved for surgery. Pairs of residents and attending physicians were assigned to three operation rooms, while Ogura sat in a nearby endoscopy room examining new cancer patients and mapping their surgery. “Between cases he would run into the operating rooms to see how everything was going,” says Spector. “When you hit a critical part of the surgery, he’d come in and take the resident or attending through it, or do it himself.

“Three rooms with three cases a day in each, plus 13 or 14 endoscopies in the side room—a total of 27 of 30 primary cancers per week,” he adds. “That’s huge—the largest volume in the world.”

With the sterling reputation of his program, Ogura had his pick of residents. Because he gave them an unusual amount of responsibility, they had to be scrupulously honest. “And he wanted the brightest kids here,” says Spector. “…it was all merit.”

Ogura showed his students what it meant to be a tough competitor. Donald Sessions recalls a game of tennis he played with Ogura. “I was a pretty good tennis player, and the first time I served against him I aced him,” he says. “He looked me straight in the eye and called it out.”

Sometimes he also would test their endurance. On surgery mornings, he arrived for work at 6 a.m. and expected the residents to be there too. But one day he came in at 5:30. So the next day they came in at 5:30—and he had been there since 5:00. The game went on until they were all arriving at 3:30, when the residents declared that Ogura had won. Then they all went back to 6 a.m.

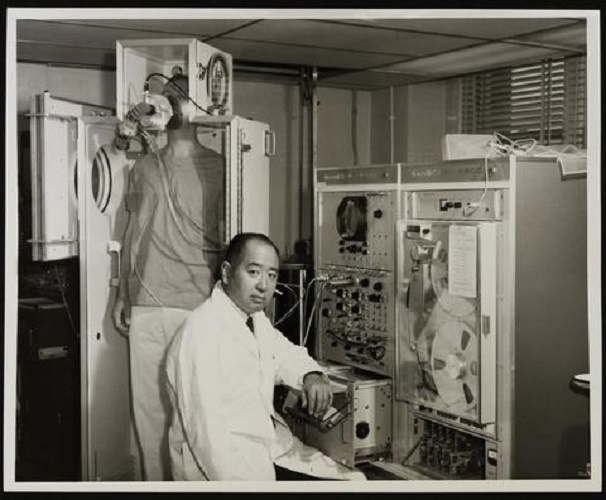

In their research, he also held them to high standards. Toshio Ohnishi, M.D., director of the Department of Otolaryngology at St. Luke’s International Hospital in Tokyo, was a research fellow for Ogura from 1966 to 1969. Ogura believed that chronic sinus disease could cause impaired lung function, and he asked Ohnishi to test this theory in animal experiments. “Although the results of my experiments were not conclusive, I learned how close I could reach to impossible by attempting ever possible way to attain my goal,” says Ohnishi.

Tough on his students, Ogura was hardest on himself. Once he went to Australia to give a lecture, recalls his wife, Ruth, and made the trip there and back in only five days. The morning after his return, he was up at 4:30 and performing surgery as usual.

When he died suddenly of a heart attack in 1983, after hospitalization for bleeding ulcers, he left his widow and three children: John, Peter and Susan. The Department of Otolaryngology’s library is now named for him, along with its prestigious annual Ogura lectureship, established in 1977.

Today, his photograph hangs in the offices of most of his former residents, whose careers have been shaped by his influence. “He was more than a person; he was a force,” says Sessions, “and everyone around him got a sense of that. He could be abrupt or polite, but what he was after was to have us be the best that we could be. And that is the source of our love for him.”