Editor’s Note: Sometime in 1995, Edith Mitchell, a U.S. Air Force oncologist who at the time served as commander of the 131st Medical Squadron at Lambert-St. Louis International Airport, first heard the name Jane Cooke Wright.

Karen Antman, then president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, wanted to know whether Mitchell, who is Black, has heard that a Black woman oncologist was among ASCO’s seven founding members.

Mitchell had no idea.

Antman reached out to Wright, inviting her to the 1995 ASCO annual meeting. Mitchell, too, reached out to Wright. This started a friendship with Wright and her family members.

Wright died on Feb. 19, 2013, at age 93.

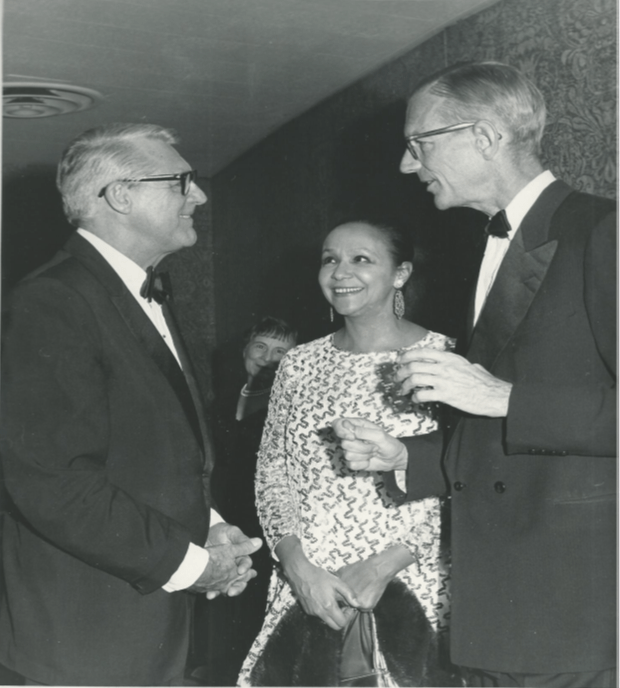

A photo archive chronicling Wright’s life is posted here.

The text of a eulogy by Mitchell, now a professor and associate director for diversity services at Thomas Jefferson University Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center, delivered on behalf of the National Medical Association at a memorial service for Wright follows.

Edith Mitchell: Good afternoon.

It is a great privilege and honor to have the opportunity to represent the National Medical Association in this tribute to Dr. Jane Cooke Wright. I first met Dr. Wright during as ASCO meeting and maintained subsequent contact.

She is affectionately known in the cancer research community as the Mother of Chemotherapy. She is not only known as the Mother of Chemotherapy, but Dr. Wright is listed in the Women Pioneers of Medical Research and among the top Medical Researchers.

As a researcher, physician, administrator, teacher, mentor, educator, her many discoveries have brought continued health into the lives of millions of people. Across the board, doctors and research scientists dedicated themselves to find cures and treatment for some of the most severe and significant diseases that have challenged mankind for many ages.

One such woman has left one such indelible mark in the world of medicine and medical disparities, not only in the fight against cancer, but, against other diseases. You have already heard and most are aware of the research accomplishments of Dr. Jane Cooke Wright, including that she is credited with developing the technique of using human tissue culture rather than laboratory mice to test the effects of potential drugs on cancer cells.

She also pioneered the use of the drug methotrexate to treat breast cancer and skin cancer. However, Dr. Wright and many of her family members were also active in the National Medical Association. It is well recognized that the National Medical Association was formed in 1895, when physicians of color could not join nor become members of the American Medical Association.

In the archives of the National Medical Association and the Journal of The National Medical Association, I found many articles and educational programs presented by Dr. Wright or other members of her family. She was the first woman physician to serve on the editorial board of the Journal of the National Medical Association.

Following the suggestion of her father, Dr. Louis T. Wright, who was chairman of the Board of the NAACP for 19 years at the time of his death in 1952, Dr. W. Montague Cobb, then editor of the Journal of the National Medical Association, wrote two pamphlets published by the NAACP in 1947 and 1948 respectively:

- The first, entitled “Medical Care and the Plight of the Negro,” was described as a horizontal analysis of the current scene of disparities in medical care in the United States.

- The second, “Progress and Portents for the Negro in Medicine,” was described as a vertical or historical picture.

Both were influential, but not popular at that time. Dr. Louis T. Wright fought for better health care, better jobs, and better education for African Americans and espoused the proposition that that one could not separate poor health from economic differences.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright was highly influenced by her father, and joined him at Harlem Hospital, overcoming both gender and racial bias. Dr. Wright’s paternal grandfather, Dr. Ceah Ketcham Wright, graduated from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn., a school renowned for educating Black physicians.

Dr. Wright’s uncle, Dr. Harold Dadford West, became the first African American president of Meharry Medical College.

In 1955, Dr. Wright joined the medical faculty at New York Medical Center as the director of cancer chemotherapy research and as an Instructor in research surgery. Her work with Jewel Plummer-Cobb led to important discoveries of cancer cells in culture. Dr. Wright later explored innovative methods of chemotherapy administration.

Later, she returned to her alma mater, New York Medical College in 1967, as associate dean and professor of surgery, and headed the Chemotherapy Department, and was ranked the highest Black American Women at a nationally recognized medical institution.

In 1971, she became the first woman elected president of the New York Cancer Society and also served on the board of directors of the American Cancer Society of New York; a founding member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; and, in 2004, a 50-year member of the American Association for Cancer Research.

Other Awards

While Dr. Wright’s cancer research made her an important role model, it is well recognized that there were others.

Dr. Wright, well known for her spectacular attire and characteristic pearl jewelry, received a prestigious Merit Award from Mademoiselle Magazine in 1952; recognition in Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP, appearing on the January 1953 cover; the Spirit of Achievement Award of the Women’s Division of Albert Einstein College of Medicine in 1961; and the Hadassah Myrtle Wreath Award in 1967.

She was appointed to the National Cancer Advisory Board (also known as the National Cancer Advisory Council) by President Lyndon Johnson, serving from 1966-1970, and President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer and Stroke. The recommendations included better communications among physicians, hospitals and research institutions and lead to development of a national network of treatment health centers.

She received honorary degrees from Women’s Medical College, now a part of Drexel University and Dennison University with honorary degrees in 1965 and 1971.

In 1975, the journal Cancer Research selected eight women scientists, printing Dr. Wright’s picture along with seven others for the cover. Ciba Geigy listed Dr. Wright on its Exceptional Black Scientist poster in 1980. Dr. Wright became an honorary member of Alpha Kappa Alpha (AKA) Sorority Inc., the first Black Sorority in America, and an organization that I am proud to be a member of.

She was also listed in Black Women of America (Beautiful are the Souls of My Black Sisters). The accomplishments of Dr. Wright place her in a category of her own as she is certainly one of a kind.

Global Medicine

Dr. Wright led delegations of oncologists to China and the Soviet Union, and countries in Africa and Eastern Europe.

She led medical teams providing medical and cancer care and education to other nurses and physicians in Ghana in 1957 and Kenya in 1961. From 1973 to 1984, she served as vice-president of the African Research and Medical foundation.

It is a great privilege to be here with her family today, Dr. Pierce, Allison and Jane, Dr. Wright’s sister and two daughters.

During her retirement years, Dr. Wright spent much of her time enjoying the company of family, friends and professional colleagues. Her favorite hobbies were watercolor painting, reading mystery stories and sailing. She was an accomplished swimmer. She spoke about her life’s work in cancer research at the 50th anniversary Smith College graduation.

It is with distinct honor and privilege that I have this opportunity to recognize a true pioneer in the field of cancer research and cancer treatment in medical affairs, medical education, humanitarian and global medicine.

She is indeed an inspiration for researchers and practitioners in the fields of oncology, but also a leader and mentor for physicians for years to come.

She was a rigorous scientific investigator, but had a very serious concern about quality patient care and provider education.

She truly has made contributions that have changed the practice of medicine. A true pioneer. A concerned mentor. A renowned researcher. A global teacher. A global medical pioneer. A talented researcher, beloved sister, wife, and mother, and a beautiful, kind, and loving human being.